What is a gastric bypass operation?

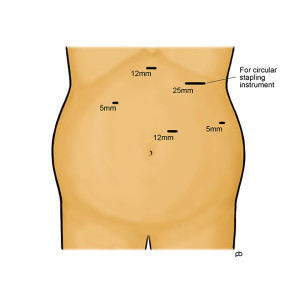

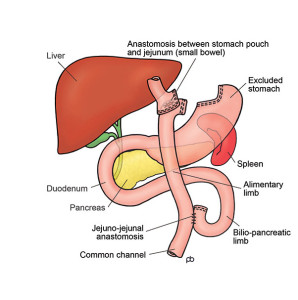

There are two type of gastric bypass surgery: the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and the one anastomosis gastric bypass. Please note that Mr Sarela does only the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The operation is done by laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) under general anaesthesia in Leeds. It takes 1½-2½ hours. The operation is done with special surgical instruments called staplers that cut and seal the walls of the stomach simultaneously. The stomach is a large sack that has a capacity of about two pints. Staplers are used to divide the stomach into two parts. The upper part of the stomach, which is connected to the oesophagus (gullet), is now called the gastric pouch. The lower, disconnected part of the stomach remains in the body and does not cause any problem. The small bowel is now joined to the upper part of the stomach. This join between the stomach and the bowel is called the gastro-jejunal anastomosis. Food enters the small stomach pouch and passes directly into the small bowel, bypassing the lower part of the stomach and the upper part of the small bowel. The small bowel is routed to the stomach in a special way called Roux-en-Y. The Roux-en-Y method involves making a join between two parts of the bowel. The join in the bowel is called the jejuno-jejunal anastomosis.

How does a gastric bypass work?

The gastric bypass gives you a feeling of fullness after eating a small meal. Also, it controls your appetite so you do not feel hungry until it is time for the next meal. These effects happen because the gastric bypass reduces the working size of your stomach. This is called the restrictive effect of operation. Also, there are changes in the levels of several hormones that control your hunger, fullness and blood sugar levels. These hormones are released from special cells in the lining of the small bowel and the stomach. Because of these changes in hormone levels, you can feel as if a switch has been turned off in your head. One of these hormones (called GLP-1) also controls blood sugar levels. In fact, injections of GLP-1 (Byetta® or Victoza®) are given to some patients with diabetes to bring down blood sugar levels. After a bypass, there can be marked increase in the release of GLP-1 from the bowel. It is like a free, internal injection of GLP-1. This is one important reason why the bypass is effective for controlling diabetes, over and above weight loss.

How much weight can I lose with the gastric bypass?

Your weight loss will depend on your starting BMI and gender. Please remember that there are no guarantees in weight loss surgery: the numbers below are rough estimates only.

If you are a woman and your BMI is less than 50, you could lose about 75% of your excess weight (%EWL). If your BMI is more than 50, the average weight loss is lower: about 60-65% EWL.

If you are a man and your BMI is less than 50, you could have 65-70%EWL . If your BMI is more than 50, the average weight loss is lower: about 60-65%EWL.

Weight loss takes place during the first year after the operation. After this time, weight-loss stops and you have reached your new weight. This new weight is called the plateau. You could imagine that the gastric bypass has reset a weigh-thermostat in your body. The gastric bypass helps you to maintain your new weight once you have reached your plateau.

What is the follow-up care for gastric bypass?

Lifelong follow-up is essential after gastric bypass. For the first 2 years after your operation, your follow-up will be with the hospital and with your GP. After 2 years, the follow-up will be primarily with your GP, but either your GP or you can contact us at any time for advice. You can think of the follow-up care in 3 parts: